Checksums and data integrity

Suggest changes

Suggest changes

ONTAP and its supported protocols include multiple features that protect Oracle database integrity, including both data at rest and data being transmitted over the network network.

Logical data protection within ONTAP consists of three key requirements:

-

Data must be protected against data corruption.

-

Data must be protected against drive failure.

-

Changes to data must be protected against loss.

These three needs are discussed in the following sections.

Network corruption: checksums

The most basic level of data protection is the checksum, which is a special error-detecting code stored alongside the data. Corruption of data during network transmission is detected with the use of a checksum and, in some instances, multiple checksums.

For example, an FC frame includes a form of checksum called a cyclic redundancy check (CRC) to make sure that the payload is not corrupted in transit. The transmitter sends both the data and the CRC of the data. The receiver of an FC frame recalculates the CRC of the received data to make sure that it matches the transmitted CRC. If the newly computed CRC does not match the CRC attached to the frame, the data is corrupt and the FC frame is discarded or rejected. An iSCSI I/O operation includes checksums at the TCP/IP and Ethernet layers, and, for extra protection, it can also include optional CRC protection at the SCSI layer. Any bit corruption on the wire is detected by the TCP layer or IP layer, which results in retransmission of the packet. As with FC, errors in the SCSI CRC result in a discard or rejection of the operation.

Drive corruption: checksums

Checksums are also used to verify the integrity of data stored on drives. Data blocks written to drives are stored with a checksum function that yields an unpredictable number that is tied to the original data. When data is read from the drive, the checksum is recomputed and compared to the stored checksum. If it does not match, then the data has become corrupt and must be recovered by the RAID layer.

Data corruption: lost writes

One of the most difficult types of corruption to detect is a lost or a misplaced write. When a write is acknowledged, it must be written to the media in the correct location. In-place data corruption is relatively easy to detect by using a simple checksum stored with the data. However, if the write is simply lost, then the prior version of data might still exist and the checksum would be correct. If the write is placed at the wrong physical location, the associated checksum would once again be valid for the stored data, even though the write has destroyed other data.

The solution to this challenge is as follows:

-

A write operation must include metadata that indicates the location where the write is expected to be found.

-

A write operation must include some sort of version identifier.

When ONTAP writes a block, it includes data on where the block belongs. If a subsequent read identifies a block, but the metadata indicates that it belongs at location 123 when it was found at location 456, then the write has been misplaced.

Detecting a wholly lost write is more difficult. The explanation is very complicated, but essentially ONTAP is storing metadata in a way that a write operation results in updates to two different locations on the drives. If a write is lost, a subsequent read of the data and associated metadata shows two different version identities. This indicates that the write was not completed by the drive.

Lost and misplaced write corruption is exceedingly rare, but, as drives continue to grow and datasets push into exabyte scale, the risk increases. Lost write detection should be included in any storage system supporting database workloads.

Drive failures: RAID, RAID DP, and RAID-TEC

If a block of data on a drive is discovered to be corrupt, or the entire drive fails and is wholly unavailable, the data must be reconstituted. This is done in ONTAP by using parity drives. Data is striped across multiple data drives, and then parity data is generated. This is stored separately from the original data.

ONTAP originally used RAID 4, which uses a single parity drive for each group of data drives. The result was that any one drive in the group could fail without resulting in data loss. If the parity drive failed, no data was damaged and a new parity drive could be constructed. If a single data drive failed, the remaining drives could be used with the parity drive to regenerate the missing data.

When drives were small, the statistical chance of two drives failing simultaneously was negligible. As drive capacities have grown, so has the time required to reconstruct data after a drive failure. This has increased the window in which a second drive failure would result in data loss. In addition, the rebuild process creates a lot of additional I/O on the surviving drives. As drives age, the risk of the additional load leading to a second drive failure also increases. Finally, even if the risk of data loss did not increase with the continued use of RAID 4, the consequences of data loss would become more severe. The more data that would be lost in the event of a RAID-group failure, the longer it would take to recover the data, extending business disruption.

These issues led NetApp to develop the NetApp RAID DP technology, a variant of RAID 6. This solution includes two parity drives, meaning that any two drives in a RAID group can fail without creating data loss. Drives have continued to grow in size, which eventually led NetApp to develop the NetApp RAID-TEC technology, which introduces a third parity drive.

Some historical database best practices recommend the use of RAID-10, also known as striped mirroring. This offers less data protection than even RAID DP because there are multiple two-disk failure scenarios, whereas in RAID DP there are none.

There are also some historical database best practices that indicate RAID-10 is preferred to RAID-4/5/6 options due to performance concerns. These recommendations sometimes refer to a RAID penalty. Although these recommendations are generally correct, they are inapplicable to the implementations of RAID within ONTAP. The performance concern is related to parity regeneration. With traditional RAID implementations, processing the routine random writes performed by a database requires multiple disk reads to regenerate the parity data and complete the write. The penalty is defined as the additional read IOPS required to perform write operations.

ONTAP does not incur a RAID penalty because writes are staged in memory where parity is generated and then written to disk as a single RAID stripe. No reads are required to complete the write operation.

In summary, when compared to RAID 10, RAID DP and RAID-TEC deliver much more usable capacity, better protection against drive failure, and no performance sacrifice.

Hardware failure protection: NVRAM

Any storage array servicing a database workload must service write operations as quickly as possible. Furthermore, a write operation must be protected from loss from an unexpected event such as a power failure. This means any write operation must be safely stored in at least two locations.

AFF and FAS systems rely on NVRAM to meet these requirements. The write process works as follows:

-

The inbound write data is stored in RAM.

-

The changes that must be made to data on disk are journaled into NVRAM on both the local and partner node. NVRAM is not a write cache; rather it is a journal similar to a database redo log. Under normal conditions, it is not read. It is only used for recovery, such as after a power failure during I/O processing.

-

The write is then acknowledged to the host.

The write process at this stage is complete from the application point of view, and the data is protected against loss because it is stored in two different locations. Eventually, the changes are written to disk, but this process is out-of-band from the application point of view because it occurs after the write is acknowledged and therefore does not affect latency. This process is once again similar to database logging. A change to the database is recorded in the redo logs as quickly as possible, and the change is then acknowledged as committed. The updates to the datafiles occur much later and do not directly affect the speed of processing.

In the event of a controller failure, the partner controller takes ownership of the required disks and replays the logged data in NVRAM to recover any I/O operations that were in-flight when the failure occurred.

Hardware failure protection: NVFAIL

As discussed earlier, a write is not acknowledged until it has been logged into local NVRAM and NVRAM on at least one other controller. This approach makes sure that a hardware failure or power outage does not result in the loss of in-flight I/O. If the local NVRAM fails or the connectivity to HA partner fails, then this in-flight data would no longer be mirrored.

If the local NVRAM reports an error, the node shuts down. This shutdown results in failover to a HA partner controller. No data is lost because the controller experiencing the failure has not acknowledged the write operation.

ONTAP does not permit a failover when the data is out of sync unless the failover is forced. Forcing a change in conditions in this manner acknowledges that data might be left behind in the original controller and that data loss is acceptable.

Databases are especially vulnerable to corruption if a failover is forced because databases maintain large internal caches of data on disk. If a forced failover occurs, previously acknowledged changes are effectively discarded. The contents of the storage array effectively jump backward in time, and the state of the database cache no longer reflects the state of the data on disk.

To protect data from this situation, ONTAP allows volumes to be configured for special protection against NVRAM failure. When triggered, this protection mechanism results in a volume entering a state called NVFAIL. This state results in I/O errors that cause a an application shutdown so that they do not use stale data. Data should not be lost because any acknowledged write should be present on the storage array.

The usual next steps are for an administrator to fully shut down the hosts before manually placing the LUNs and volumes back online again. Although these steps can involve some work, this approach is the safest way to make sure of data integrity. Not all data requires this protection, which is why NVFAIL behavior can be configured on a volume-by-volume basis.

Site and shelf failure protection: SyncMirror and plexes

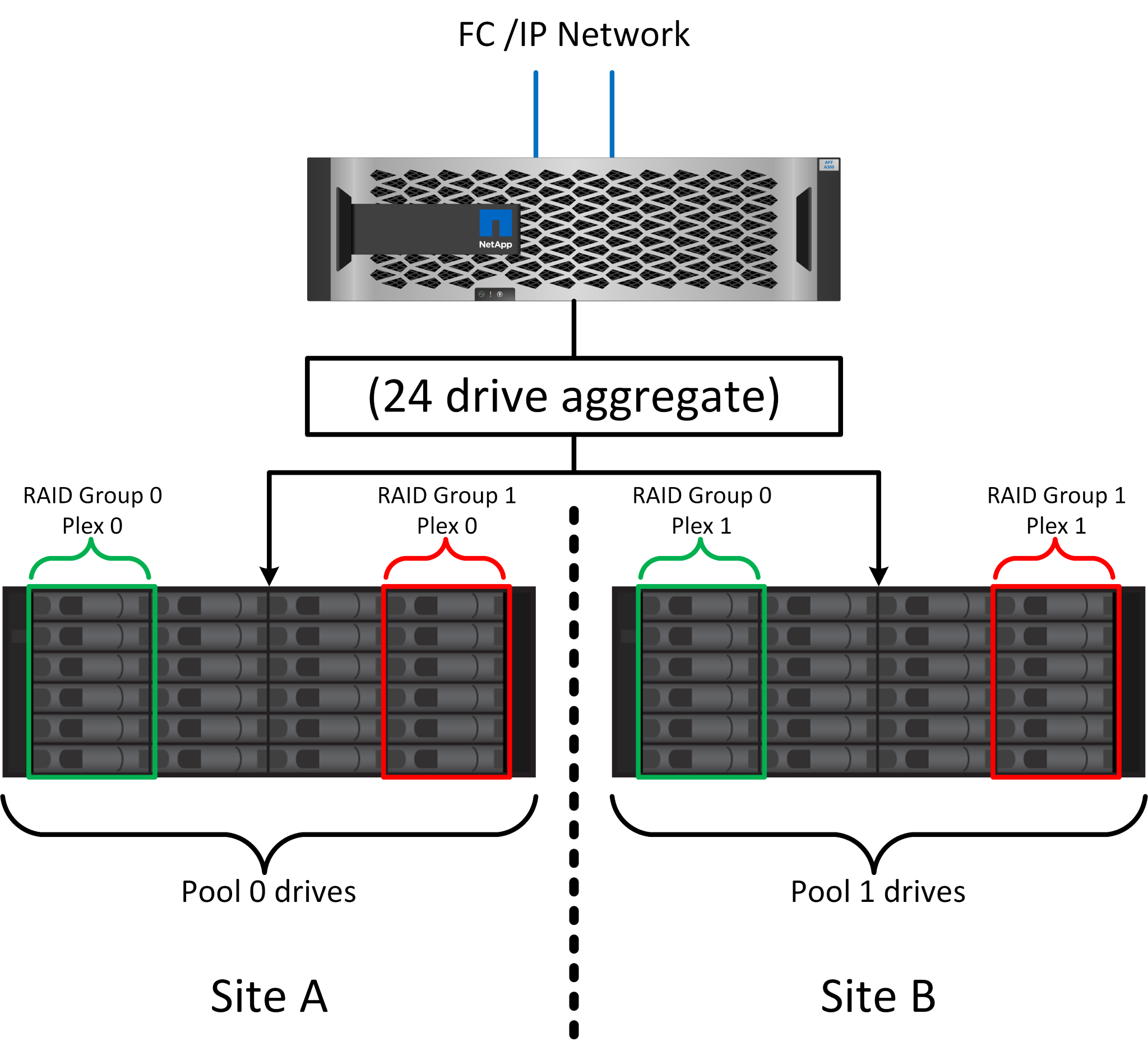

SyncMirror is a mirroring technology that enhances, but does not replace, RAID DP or RAID-TEC. It mirrors the contents of two independent RAID groups. The logical configuration is as follows:

-

Drives are configured into two pools based on location. One pool is composed of all drives on site A, and the second pool is composed of all drives on site B.

-

A common pool of storage, known as an aggregate, is then created based on mirrored sets of RAID groups. An equal number of drives is drawn from each site. For example, a 20-drive SyncMirror aggregate would be composed of 10 drives from site A and 10 drives from site B.

-

Each set of drives on a given site is automatically configured as one or more fully redundant RAID-DP or RAID-TEC groups, independent of the use of mirroring. This provides continuous data protection, even after the loss of a site.

The figure above illustrates a sample SyncMirror configuration. A 24-drive aggregate was created on the controller with 12 drives from a shelf allocated on Site A and 12 drives from a shelf allocated on Site B. The drives were grouped into two mirrored RAID groups. RAID Group 0 includes a 6-drive plex on Site A mirrored to a 6-drive plex on Site B. Likewise, RAID Group 1 includes a 6-drive plex on Site A mirrored to a 6-drive plex on Site B.

SyncMirror is normally used to provide remote mirroring with MetroCluster systems, with one copy of the data at each site. On occasion, it has been used to provide an extra level of redundancy in a single system. In particular, it provides shelf-level redundancy. A drive shelf already contains dual power supplies and controllers and is overall little more than sheet metal, but in some cases the extra protection might be warranted. For example, one NetApp customer has deployed SyncMirror for a mobile real-time analytics platform used during automotive testing. The system was separated into two physical racks supplied by independent power feeds from independent UPS systems.

Checksums

The topic of checksums is of particular interest to DBAs who are accustomed to using Oracle RMAN streaming backups migrates to snapshot-based backups. One feature of RMAN is that it performs integrity checks during backup operations. Although this feature has some value, its primary benefit is for a database that is not used on a modern storage array. When physical drives are used for an Oracle database, it is nearly certain that corruption eventually occurs as the drives age, a problem that is addressed by array-based checksums in true storage arrays.

With a real storage array, data integrity is protected by using checksums at multiple levels. If data is corrupted in an IP-based network, the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) layer rejects the packet data and requests retransmission. The FC protocol includes checksums, as does encapsulated SCSI data. After it is on the array, ONTAP has RAID and checksum protection. Corruption can occur, but, as in most enterprise arrays, it is detected and corrected. Typically, an entire drive fails, prompting a RAID rebuild, and database integrity is unaffected. It is still possible for individual bytes on a drive to be damaged by cosmic radiation or failing flash cells. If this happens, the parity check would fail, the drive would be failed out and a RAID rebuild would begin. Once again, data integrity is unaffected. The final line of defense is the use of checksums. If, for example, a catastrophic firmware error on a drive corrupted data in a way that somehow was not detected by a RAID parity check, the checksum would not match and ONTAP would prevent the transfer of a corrupted block before the Oracle database could receive it.

The Oracle datafile and redo log architecture is also designed to deliver the highest possible level of data integrity, even under extreme circumstances. At the most basic level, Oracle blocks include checksum and basic logical checks with almost every I/O. If Oracle has not crashed or taken a tablespace offline, then the data is intact. The degree of data integrity checking is adjustable, and Oracle can also be configured to confirm writes. As a result, almost all crash and failure scenarios can be recovered, and in the extremely rare event of an unrecoverable situation, corruption is promptly detected.

Most NetApp customers using Oracle databases discontinue the use of RMAN and other backup products after migrating to snapshot-based backups. There are still options in which RMAN can be used to perform block-level recovery with SnapCenter. However, on a day-to-day basis, RMAN, NetBackup, and other products are only used occasionally to create monthly or quarterly archival copies.

Some customers choose to run dbv periodically to perform integrity checks on their existing databases. NetApp discourages this practice because it creates unnecessary I/O load. As discussed above, if the database was not previously experiencing problems, the chance of dbv detecting a problem is close to zero, and this utility creates a very high sequential I/O load on the network and storage system. Unless there is reason to believe corruption exists, such as exposure to a known Oracle bug, there is no reason to run dbv.