Cybersecurity threats in healthcare

Suggest changes

Suggest changes

Every problem presents a new opportunity—an example of one such opportunity is presented by the COVID pandemic. According to a report by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Cybersecurity Program, the COVID response has resulted in an increased number of ransomware attacks. There were 6,000 new internet domains registered just in the third week of March 2020. More than 50% of the domains hosted malware. Ransomware attacks were responsible for almost 50% of all healthcare data breaches in 2020 affecting more than 630 healthcare organizations and approximately 29 million healthcare records. Nineteen leakers/sites doubled the extortion. At 24.5%, the healthcare industry saw the highest number of data breaches in 2020.

Malicious agents attempted to breach security and privacy of Protected Health Information (PHI) by selling the information or by threatening to destroy or expose it. Targeted and mass-broadcast attempts are frequently made to gain unauthorized access to ePHI. Approximately 75% of the exposed patient records in the second half of 2020 were due to compromised business associates.

The following list of healthcare organizations were targeted by the malicious agents:

-

Hospital systems

-

Life science labs

-

Research labs

-

Rehabilitation facilities

-

Community hospitals and clinics

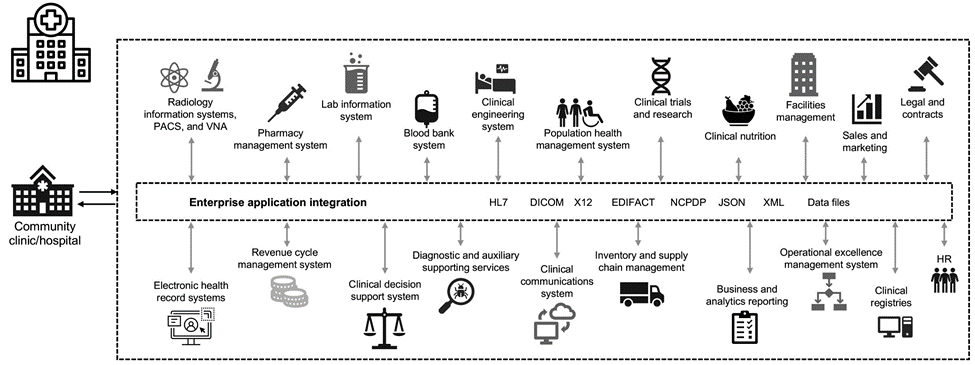

The diversity of applications that constitute a healthcare organization is undeniable and increasingly growing in complexity. Information security offices are challenged to provide governance for the vast array of IT systems and assets. The following figure depicts the clinical capabilities of a typical hospital system.

Patient data is at the heart of this image. The loss of patient data and the stigma associated with sensitive medical conditions is very real. Other sensitive issues include the risk of social exclusion, blackmail, profiling, vulnerability to targeted marketing, exploitation, and potential financial liability toward payers about medical information beyond the payer’s privileges.

Threats to healthcare are multidimensional in nature and in impact. Governments worldwide have enacted various provisions to secure ePHI. The detrimental effects and the evolving nature of the threats to healthcare make it difficult for healthcare organizations to defend all threats.

Here is a list of common threats identified in healthcare:

-

Ransomware attacks

-

Loss or theft of equipment or data with sensitive information

-

Phishing attacks

-

Attacks against connected medical devices that can affect patient safety

-

E-mail phishing attacks

-

Loss or theft of equipment or data

-

Remote desktop protocol compromise

-

Software vulnerability

Healthcare organizations operate in a legal and regulatory environment that is as complicated as their digital ecosystems. This environment includes, but is not limited to, the following:

-

Office of the National Coordinator (for Healthcare Technology) ONC Certified Electronic Health Information Technology interoperability standards

-

Medicare access and the children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (MACRA)/Meaningful Use

-

Multiple obligations under the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

-

The Joint Commission accreditation processes

-

HIPAA requirements

-

HITECH requirements

-

Minimum Acceptable Risk Standards for payers

-

State privacy and security rules

-

Federal Information Security Modernization Act requirements as incorporated into federal contracts and research grants through agencies such as the National Institutes of Health

-

Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS)

-

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) requirements

-

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act for financial processing

-

The Stark Law as it relates to providing services to affiliated organizations

-

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) for institutions that participate in higher education

-

Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA)

-

The new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union

Security architecture standards are fast evolving to stop the malicious actors from impacting healthcare information systems. One such standard is FIPS 140-2, defined by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). FIPS publication 140-2 details the U.S. government requirements for a cryptographic module. The security requirements cover areas related to a secure design and implementation of a cryptographic module and can be applied to HIT. Well-defined cryptographic boundaries allow for easier security management while staying current with the cryptographic modules. These boundaries help prevent weak crypto modules that can be easily exploited by malicious actors. They can also help prevent human errors when managing standard cryptographic modules.

NIST along with the Communications Security Establishment (CSE) have established the Cryptographic Module Validation Program (CMVP) to certify cryptographic modules for FIPS 140-2 validation levels. Using a FIPS 140-2 certified module, federal organizations are required to protect sensitive or valuable data while at-rest as well as while in motion. Due to its success in protecting sensitive or valuable information, many healthcare systems have chosen to encrypt ePHI by using FIPS 140-2 cryptographic modules beyond the legally required minimum level of security.

Leveraging and implementing the FlexPod FIPS 140-2 capabilities only takes hours (not days). Becoming FIPS compliant is within reach for most healthcare organizations, regardless of size. With clearly defined cryptographic boundaries and well-documented and simple implementation steps, a FIPS 140-2 compliant FlexPod architecture can set a solid security foundation for infrastructure and allow for simple enhancements to further increase protection for security threats.